Architect Ming Thompson Designs spaces and her life

Growing up, architect Ming Thompson spent hours making craft projects. When she got to college, a class on structural physics in architecture, making pasta towers and stick bridges, connected the dots between her love of making things with a profession dedicated to doing just that. Today she and a partner run their own architecture and design firm, where they design physical spaces, graphics, and anything in-between- while they design the business and life they want. As Ming tells us, “If I can be in a position where I’m making things or designing things I’m pretty happy.”

FAST FACTS ABOUT Ming

Where she’s from: "Deep Southwestern Virginia"

Grew up with: mom and dad and younger brother

Education: BA in Architecture from Yale University; M. Architecture from Harvard Graduate School of Design

Where she lives now: San Francisco, California

Growing up she wanted to be: making things

Now she’s: an architect with her own design firm

Tell us about yourself growing up!

When I was a kid I always really liked to make things. I had lots of these boxes that are for fishing lures that were filled with different craft things. I would sit by myself and make dolls and purses and clothes and these little gadgets and toys.

I always really liked school. I liked structure and knowing what you’re supposed to do and that there was an agenda every day. I was pretty easygoing.

I grew up in a small town around people who have lots of different types of jobs, who are from different classes, who are from different backgrounds in a small town. That was really good for me as a child to go to public school and to be around lots of different types of people.

How did you end up going to boarding school?

My local high school was not very challenging. I loved school and I was looking for something that was more rigorous. My dad and his brothers and my grandmother and her siblings had all gone to boarding school, so it was in the air that it was a possibility. I read about a few schools all in Virginia or in the DC area and Madeira seemed really interesting. It’s really appealing that [through the Co-Curriculum program] they teach that achievement in a scholastic setting is not the only tool that you need to succeed as an adult. It’s also about being able to be in a workplace, being able to communicate with people in real world settings like congressional offices or nonprofit art centers.

My Parents being entrepreneurs made me want to be an entrepreneur.

Who were the adults that were important in your life when you were growing up?

Definitely my parents. My parents started a restaurant in my family’s old dairy barn in the ’70s, and it grew into this wild success that is a really creative and eclectic and fascinating place. Them being entrepreneurs made me want to be an entrepreneur. You get to create something from nothing that will have an impact on someone’s life that will make them feel a certain way or have certain experiences. That’s really incredible to create something where there was nothing before. I realized I’m trying to emulate what they did with their lives as I get older.

How did you get interested in architecture?

Yale has such a wonderful history program I thought I was going to be a history major. Then one of my best friends was taking a class in architecture. I’d never known an architect or knew what an architect did. I took the class with him and it was structural physics for architecture. We made bridges out of pasta and towers out of sticks. It was so fun to be able to use math and a very structured art at the same time. I really loved it. Architecture is interesting because it’s highly analytical but it’s also creative.

Then I took the introduction to the study of architecture. I remember the professor talking about how sidewalks were made. I had this epiphany where I realized that every single thing in the world was a product of someone’s analysis and creativity. I thought that was amazing that the built environment is a human creation. I was excited to be able to be a part of that. I realized that the things that I love doing, which were making things, were something that you could do as a career. There was a way to make things that were practical and useful as an architect.

If I can be in a position where I’m making things or designing things I’m pretty happy.

Did you decide then that you wanted to be an architect?

I decided to become an architecture major. Once you’re an architecture major you get to take these great classes called studios where you spend a lot of time in the studio with your fellow students working on design projects. You get a desk in the architecture school and you’re there all the time, often all night long, to solve these design problems. You’re doing drawings; you’re making things on the computer; you’re building models; you’re learning about tools; and you’re collaborating with teammates to create design solutions.

At the same time, I’ve always loved museums. I really love how people can get educated or inspired by great works of art. In high school I worked in the National Gallery, and in college I worked at the Yale Art Gallery and the Guggenheim in Venice. At the end of college I was debating, “Do I want to be an architect or do I want to go into museum work?” I decided that it came back to the idea of making things. That has become the guiding principle of my career. If I can be in a position where I’m making things or designing things I’m pretty happy.

Did you go straight into architecture school?

You’ve got the rest of your life to work and go to school, but there’s this precious little time right after college where you’re allowed to be free and explore the world. It’s a great time to go live life in a different way and see how people live in a different part of the world. I’ve always found China very interesting. I found this fellowship at Yale to teach in China for two years, so I went. You’re with this amazing group of people and you are learning a lot about China and learning a lot about what it means to be an American and learning how to teach Chinese middle school students. It was a really incredible experience.

The whole time I knew that when I went back I was going to go to architecture school. I came back and went into architecture school.

Did you have an idea of what kind of work you wanted to do going into grad school?

I find that I do better and I flourish in the real world where there’s a client with demands or there’s a budget with a limit or there’s a schedule that must be met. In school there are none of those parameters so you’re just designing freely and that doesn’t work very well for me. It was only after I graduated that I really figured out what I wanted to do.

What did you do after you finished graduate school?

I’ve always really gravitated to small things that are very detailed but I asked a lot of friends who are more experienced than me and many of them said, “The thing you need to do is learn about how to put a set of construction documents together.” That’s the set of blueprints that an architect puts together so that a contractor can build a building. There’s a lot of very technical skills involved and thousands of tiny technical details that go into building construction documents.

I went to this great firm called Bolin Cywinski Jackson, which has offices all over the country. They are great, classic American architects, well-detailed, beautiful, warm modernism. In San Francisco they work with a bunch of really interesting clients. When I was there I worked mainly on Apple retail stores around the world. I learned a lot about how architecture comes together from the detail, like how does a stainless steel panel hang from the substructure to the coordination of a project, how an architect works with the mechanical engineer and a structural engineer to design the project.

Grad school is about design concepts and being able to build an argument for design projects and you don’t really learn those real world skills about how to put together a drawing set. Those three years at that firm were almost my second grad school for architecture, to really learn about the important technical aspects of how things get built, which is what architecture should be about.

You’re a licensed architect. What does that mean?

Architecture is a very, very old career and it’s a very, very traditional profession. You can’t call yourself an architect unless you are licensed by a state. To be licensed by a state you have to meet all these requirements. You have to take a series of tests, you have to do an internship for a number of years, you have to work a number of certain hours in different skillsets, and you have to have an accredited degree. My first degree in architecture was not a professional degree. It was a BA in architecture. I had to go to grad school to do that.

For me it was really important to be able to call myself an architect and be part of a defined profession. It was about meeting the challenge. Also as a young woman starting my own firm, having that credential shows that I’m serious and hardworking and that I’m past all the requirements to join the profession.

There’s something really invigorating about working between scales that you can’t really get in architecture as it’s practiced in most firms.

You now have your own firm, Atelier Cho Thompson with Christina Cho Yoo. How did you decide to join forces and start your own firm?

My whole life I’ve been interested in making lots of types of things, making graphics, making jewelry, making furniture, and then making buildings. Architecture in its traditional form is really about making the buildings. Making buildings takes a long time and big teams of people and as a young architect you’re often quite distant from the process of actually building. Most of your time you’re at a computer doing drawings.

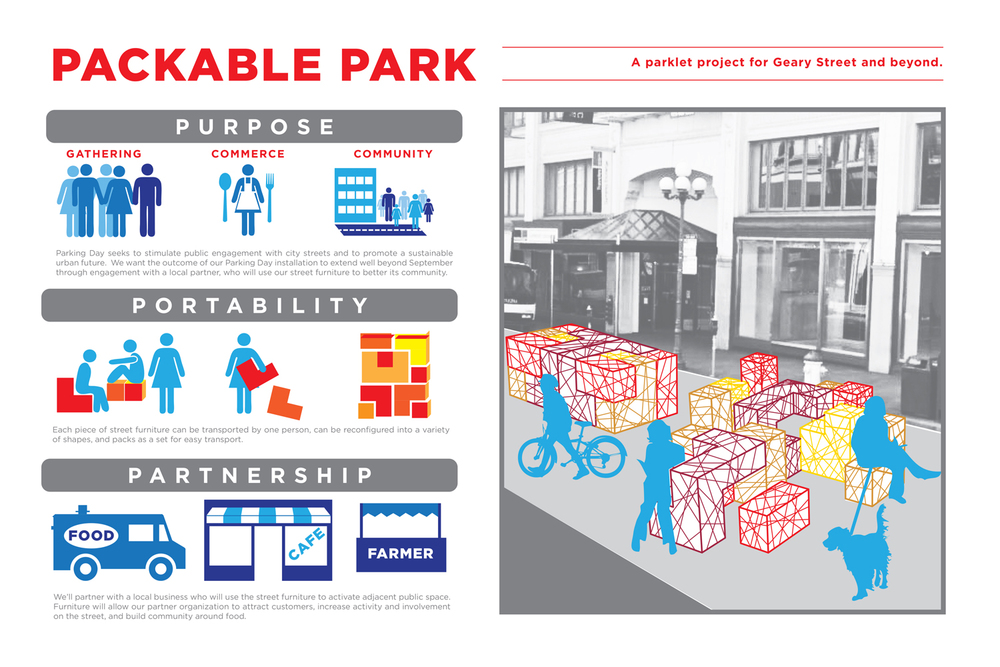

My partner and I met in grad school and then we were working at the same firm together here. For an office event there was a competition to design something for Parking Day. Parking Day is this really cool event where you take over a parking space. You reclaim it for the pedestrian for the day and you design some cool installation for that spot. We entered the competition and ended up winning. We had a lot of fun working on this project and realized that we loved this in between scale where we got to make a whole space for people to inhabit on the street but we also got to design individual pieces of furniture and graphics to advertise the events. We got to invite food trucks and design the whole event production for the day. There’s something really invigorating about working between scales that you can’t really get in architecture as it’s practiced in most firms.

For Spice Kit, a San Francisco restaurant, Atelier Cho Thompson provided Architecture, Branding/Graphics, Signage, and Interior Design services, helping the restaurant's owners define their voice and brand.

We decided that it meant that we could expand our definition of architecture to include all of these other disciplines. We decided to found a firm that was cross-disciplinary and that would use design and all of these different scales to make a richer end product. We tried to find clients that will work with us between these scales. Today, we were at a restaurant where we just did some architecture and interior remodeling, but we’ve also done graphic design for them and branding. For us, the logo and the interior design should all work together. We found that there’s a need for this and sometimes people are looking for a one-stop shop for designers that they can go to that can really help them realize a total aesthetic vision from the logo to the website to the interiors to the architecture.

What has it been like being an entrepreneur?

It’s really fun. You become a designer because you want to design things and now we spend a little bit less time designing, but we’re also designing our firm and designing our lives. We are both really interested in the practical aspects of running a business- accounting, insurance, contracts- and you have to be, because you end up spending 30 to 50 percent of your time doing the administration to keep the firm running.

I love that I don’t spend all day at a computer anymore. It’s great to be able to get up, talk to people, go to project sites, go visit furniture show rooms, go meet with a contractor and be out in the world a lot more than I used to.

I often feel like my mind is just racing, abuzz with all the amazing ideas that we are a part of.

Ming outside a tiny house Atelier Cho Thompson designed for an Oakland, CA family.

Who are the people you work with outside of your firm?

On a daily basis we could be going to a planning department and meeting with the planner to get a permit for a project. We could be going to a nursery and meeting with someone to buy plants to design a green wall. We could be meeting with students at a school where we’re designing a project to get feedback on what they want in their school. Our clients range from teachers to administrators to a chef to stay-at-home parents to venture capitalists. We get to meet a lot of different people every day. I often feel like my mind is just racing, abuzz with all the amazing ideas that we are a part of.

One moment I’m designing something for a school cafeteria and another moment designing something for a venture capitalist’s office. I get to learn about what they do and what the new and exciting ideas are in their field. I really love that I get to, as an architect be a part of a lot of different things that are happening in the world.

What keeps you excited about your work?

It’s all the possibilities, all the projects we’re a part of. Our time is very limited, but we keep coming up against projects that are so interesting to us that we just have to do them. We are looking at projects where we’re putting undergrad collaboration areas at a university or a new modern farmhouse project in California or a book on early childhood education that needs graphic design in New York. It’s all these fresh ideas that we get to encounter by people who are coming up with really brilliant and really energizing new ideas in their profession that we get to be a part of that. That’s really exciting and energizing.

Some projects focus only on design. Atelier Cho Thompson took data collected Equity by Design, a San Francisco-based advocacy group, on equity in architectural practice and turned it into rich and compelling graphics and infographics.

What fills your time outside of work?

Only work. Being an entrepreneur, the boundaries are really blurred. I have to make very efficient use of my time. When I was younger at my job my mind might drift or I might open the New York Times website and now I have to be 100 percent productive all the time. That means that I’m still reading emails at 2 a.m. and I take phone calls from clients on the weekend. Because we’re in a phase of really growing this business and taking on a lot of really interesting projects, it means that work never ends. But for me, that’s also not a bad thing. I think of it as work / life integration, finding ways that either you can pursue your life interest in your work or in your volunteer work.

I have a son and he occupies the rest of my time. Basically it’s baby and work and that’s about it these days.

When you have your own business you can leave work every day at 3:30 and then do a little extra work at nighttime or on the weekend if you need to make up for it. There is a lot more ability to be where I want when I need to and still get my work done and spend time with my son.

If you can figure out how you want to spend your days and how you want your work and life to be related, you can shape a career around that.

What advice would you give somebody that is interested in making things?

It’s good to spend your time as a student and as a young person exploring lots of different disciplines and places in the world to see what people are doing. When I was a kid, I didn’t know any architects, but if I had I would have known a bit earlier about what the possibilities are. We’re in a very lucky time now because of the interconnectedness of the world where if there’s something that you’re really passionate about, you might be able to turn that into a career. If you can figure out how you want to spend your days and how you want your work and life to be related, you can shape a career around that.

When my partner and I are facing business decisions, instead of saying, “What should we do? Should we rent this new office space or not?” we think more about, “What do we want our lives to be like? What do we want on a daily basis to be spending our time on and how do we want our work and life to be related to each other?” That’s helped solve a lot of our questions.

If you’re pursuing something in your life and other people think it’s silly or other people don’t understand it, you should definitely not abandon that. In the end all those dots will connect those things that are important to you. You will find something that you’re really passionate about and that you’re really good at and you can make a place in the world for what you want to do.

How does your life now compare to what you thought it might be like when you were a teenager?

It’s actually pretty close to what I thought it would be like. When I was in high school I left a small town to go to boarding school in a metropolitan area. At the time, the world felt very full of possibilities and new ideas. I encountered a lot of new types of people from new types of places with new types of ideas. That was so exciting and stimulating. I’ve been lucky to be able to create a life where I still feel like that. Every day is exciting. I feel overwhelmed with all of the new ideas that are happening out in the world. I never feel bored. I feel the opposite of bored, whatever that is.

This interview has been edited and condensed.